Exploring & documenting historic temples, tabernacles and chapels of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (also known as the LDS or Mormon Church).

Sunday, April 30, 2017

Sunday, April 23, 2017

Smithfield Tabernacle

The Smithfield Tabernacle took about 20 years to build--it was started in 1881, and not finished until 1902. It was finally dedicated in 1906.

|

| (Image Source: Church History Library) |

|

| (Image Source: Church History Library) |

|

| (Image Source: Church History Library) |

Recently, the city initiated a study concerning the tabernacle and its future. It was determined that it will cost over $1 million to remodel the tabernacle, no matter what it turns into. Fortunately, the study strongly encouraged the city to restore the building to its original appearance, including its windows and spires. No final decision has been made yet--government moves slow--but I hope that this building can be preserved and restored.

Tuesday, April 18, 2017

Preservation Update: Idaho Falls Temple Renovation Complete

Note: Preservation Updates are a regularly occurring series of posts where I round up recent information on historic LDS buildings and their futures. Depending on the age of the post, there may be newer information available. Click here to see all Preservation Updates.

Yesterday, the Mormon Newsroom posted an article stating that the Idaho Falls Temple renovation is now complete. I have taken the photos posted there and added them to the other photos on the post that gives an interior tour of the temple. If you want to see the temple from top to bottom, check out that post; this post focuses on the results of the renovation.

I am ecstatic to see the results of this renovation. Once the Church has decided that one of its temples or chapels is architecturally significant, it does a fabulous job of restoring and preserving that architecture, and this is clearly visible in Idaho Falls. Most of the work is unseen--retrofitting and stabilizing the building so that it can be preserved and enjoyed by Latter-day Saints for years to come.

The most obvious change to long-time patrons of the temple will be the murals, which have been carefully restored. They are more vibrant than ever, because they have been carefully cleaned and repaired.

One change I particularly like--at least, from the photos that I can see--is that the curtains are now opened in the creation, garden, and world rooms of the temple. When I visited, these curtains were shut during the entire session--ostensibly to allow the film to be viewed. I'm hoping these curtains can automatically open and close, depending on when the film is being used, to maximize the use of natural light.

I might have one concern--the ceiling of the creation room would light up with stars at the appropriate moment of the ceremony. I can't tell if this ceiling still allows that. I hope so; it certainly wasn't original to the temple, but it was a beautiful touch.

One notable change has been the reduction in the number of seats in each ordinance room. This may seem confusing--why reduce capacity? In truth, I wish this was done in all historic temples. These temples were not built to be efficient or to pus through huge numbers of patrons. When I visited this temple, there was precious little leg space (or seat width), and the large number of patrons in the session meant that it was one of the longest sessions I'd ever attended. With the increase in the number of temples--this area of Idaho now has temples in Twin Falls, Rexburg, and Star Valley (Wyoming), and there will be a temple in Pocatello. The temple doesn't need to have the huge capacity that it had before; it wasn't built for that.

This renovation, from what I can tell, has also increased the amount of natural light in the celestial room, perhaps by uncovering some original windows:

I really love this temple and the careful renovation the Church has undertaken. The Salt Lake, Manti, Cardston, and Laie Temples have been carefully preserved as well. It remains to be seen when the Church will undertake the laborious but necessary job of restoring the temples in Mesa, St. George, and especially Logan. Until then, we can enjoy this temple for the coming decades as a wonderful example of what architecture the Church can produce.

Yesterday, the Mormon Newsroom posted an article stating that the Idaho Falls Temple renovation is now complete. I have taken the photos posted there and added them to the other photos on the post that gives an interior tour of the temple. If you want to see the temple from top to bottom, check out that post; this post focuses on the results of the renovation.

I am ecstatic to see the results of this renovation. Once the Church has decided that one of its temples or chapels is architecturally significant, it does a fabulous job of restoring and preserving that architecture, and this is clearly visible in Idaho Falls. Most of the work is unseen--retrofitting and stabilizing the building so that it can be preserved and enjoyed by Latter-day Saints for years to come.

The most obvious change to long-time patrons of the temple will be the murals, which have been carefully restored. They are more vibrant than ever, because they have been carefully cleaned and repaired.

One change I particularly like--at least, from the photos that I can see--is that the curtains are now opened in the creation, garden, and world rooms of the temple. When I visited, these curtains were shut during the entire session--ostensibly to allow the film to be viewed. I'm hoping these curtains can automatically open and close, depending on when the film is being used, to maximize the use of natural light.

I might have one concern--the ceiling of the creation room would light up with stars at the appropriate moment of the ceremony. I can't tell if this ceiling still allows that. I hope so; it certainly wasn't original to the temple, but it was a beautiful touch.

One notable change has been the reduction in the number of seats in each ordinance room. This may seem confusing--why reduce capacity? In truth, I wish this was done in all historic temples. These temples were not built to be efficient or to pus through huge numbers of patrons. When I visited this temple, there was precious little leg space (or seat width), and the large number of patrons in the session meant that it was one of the longest sessions I'd ever attended. With the increase in the number of temples--this area of Idaho now has temples in Twin Falls, Rexburg, and Star Valley (Wyoming), and there will be a temple in Pocatello. The temple doesn't need to have the huge capacity that it had before; it wasn't built for that.

This renovation, from what I can tell, has also increased the amount of natural light in the celestial room, perhaps by uncovering some original windows:

I really love this temple and the careful renovation the Church has undertaken. The Salt Lake, Manti, Cardston, and Laie Temples have been carefully preserved as well. It remains to be seen when the Church will undertake the laborious but necessary job of restoring the temples in Mesa, St. George, and especially Logan. Until then, we can enjoy this temple for the coming decades as a wonderful example of what architecture the Church can produce.

Sunday, April 16, 2017

Preston First Ward

|

| (Image Source: Church History Library) |

This building was included on Richard Jackson's list of tabernacles.

Sunday, April 9, 2017

Latter-day Stained Glass: Part 10 – From Chapels to Temples: the Future of Stained Glass

Note: This is a the final part of a series on the history of the use of stained glass in LDS meetinghouses. To see a full list of the posts in this series, click here.

In the Part 2 of this series, I mentioned how the use of stained glass in the Salt Lake Temple--particularly the window of the First Vision in the Holy of Holies--helped contribute to the use of stained glass in chapels, as large, magnificent copies of the windows were placed in chapels in Salt Lake that eventually extended to other chapels along the Mormon Corridor. Prior to that time, most stained glass depictions had been fairly simple in design, due to financial constraints; the copies of the window in the temple marked the start of a new era in stained glass, when larger, more expensive, and more ornate windows graced LDS chapels.

However, during the peak era of stained glass in chapels (1900-1940), stained glass was not used in temples. Temples in St. George and Manti did not have stained glass; the Logan Temple had some stained glass, but this was likely not original to the building (I believe it was added sometime in the early 20th century. The Manti Temple also has some stained glass in the cafeteria, but this is not original to the building).

Similarly, the temples in Cardston, Laie, Mesa, Idaho Falls, Switzerland, Los Angeles, New Zealand, London, Oakland, Ogden, and Provo--temples built between 1919 and 1972--had no stained glass. (Again, the Laie Hawaii and Idaho Falls Temple now have stained glass, but I don't believe this was original; if it was, these temples were the exceptions.) While stained glass was flourishing in LDS chapels (at least, comparative to other eras), it wasn't present in temples. I believe this was due to the way that the Church viewed its architecture at the time. Chapels, when possible, mimicked the traditional great cathedrals--gothic arches, corner towers, delicate stained glass. Temples were an architecture all of their own; more attention was paid to room arrangement and symbolism than the need for stained glass. Additionally, temples were much larger than chapels; they would require much more stained glass to replace all of their windows. Finally, general architectural trends were going away from the use of stained glass after 1950. The Church is often criticized for phasing out the use of stained glass, but it was happening in multiple denominations. Whatever the reason, no stained glass was used in those temples.

The temple in Washington D.C. (dedicated in 1974) was among the first to introduce the use of stained glass again, having tall, narrow windows of stained glass along the end. Unsurprisingly, this came at a time when the Church had centralized its meetinghouse architecture, which all but eliminated the use of stained glass in chapels. Modern stained glass was added to the Tokyo Japan and Jordan River Temples (dedicatd in 1980 and 1981, respectively), as well.

These steps to re-introduce the use of stained glass were threatened in April 1980, when the Church announced the use of a new standard plan for its temples. This was the beginning of the Church's emphasis on bringing the temples to the people; when the temples were announced, the Temple Department's directors said that “We’ve entered a new era of temples...The emphasis now is on the locality. A different type of sacrifice will be required of people.” Instead of large, cathedral-like temples--which were much more likely to have stained glass put into them--smaller, more economical ones were built. After the announcement, one writer worried: "[The temple standard plan] could eventually establish a new relationship between temple and meetinghouse architecture. Whereas previous architectural style, size and materials had distinguished the temple from the ward meetinghouse, the new temples narrow the gap between these two main forms. The exterior of the temples in no way reveals the unique ceremonies within, and they have no visual articulation, towers, stained glass art windows or other features to distinguish their sacred functions..." Fortunately, a later revision to the plan added towers to the buildings, and some of them even got some form of stained glass windows.

Still, the majority of temples built in the 1980s did not have stained glass. The "six-spire" standard plan, which can be seen in temples from South Africa to Guatemala, did not have stained glass windows. The plan for local temples might have wiped out stained glass from future temples if it weren't for a shift around 1990. Temples in Denver, Toronto, Las Vegas, and San Diego all had stained glass installed. In fact, virtually every temple after the Las Vegas Temple (dedicated in late 1989) has had stained glass in some form. This was right around the era that Gordon B. Hinckley was taking charge in temple policy for the Church--either as president himself, or acting in behalf of Ezra Taft Benson, who was ill in his old age. Whether the change came from Hinckley, from new plans in the Temple Department, or from other sources, stained glass suddenly became a necessity in the Church. It could be that the finances of the Church had improved enough to allow stained glass in nearly all temples.

This was fortunate, because it meant that most of the very small temples--dedicated around 2000, when the Church initiated a push to have 100 temples--had some form of stained glass. Of course, these windows were fairly simple, and nearly identical between temples.

However, it should be noted that most of the stained glass now placed in temples is patterned glass--it is much rarer to have stained glass depicting scenes, as was common at the beginning of the twentieth century. There are some exceptions; however. The Palmyra Temple has a window depicting the First Vision.

The Winter Quarters Temple has icons and scenes that add to the temple's symbolism.

The Nauvoo Temple has a stained glass window in its baptistry showing Christ's baptism.

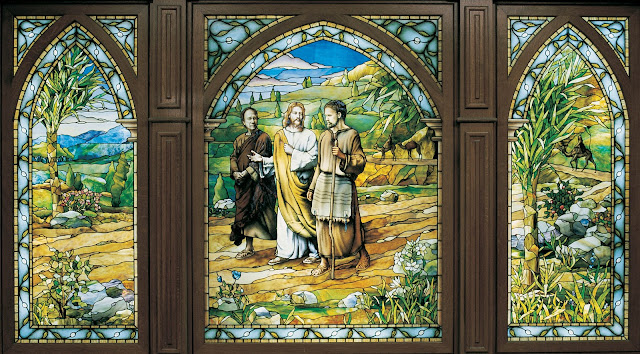

The Manhattan Temple has a window showing Christ and two disciples on the road to Emmaus.

The temple in San Antonio Texas has huge, colorful windows in many places that show scenes symbolic of different aspects of the Gospel of Jesus Christ.

And the temple in Sao Paulo Brazil had a stained glass scene installed during its 2004 renovation, depicting Christ appearing in the Americas.

Other temples had stained glass installed from different churches--temples in Vernal, Snowflake, Star Valley, and other locations have stained glass that came from different denominations. The Church has since acquired these windows and used them.

I am glad that the use of stained glass has returned to temples, with only two concerns: one is that the use of stained glass to depict scenes has declined drastically in recent history. If you exempt the windows that the Church acquired and used from other churches, then the last temple to use stained glass in this way was the temple in San Antonio, Texas--built in 2005. Even those scenes do not have people in them. The Church uses stained glass, but only patterned glass. Why have we shifted away from the stained glass depicting Christ, the First Vision, and other scriptural stories?

The other concern is that almost all of the Church's stained glass in recent history--especially the windows depicting events--comes from Tom Holdman studios. Holdman does good work, and its Mormon background probably makes it a safe option for the Church, but I worry that we are taking away from the diversity of art in the Church by only using one place for most of our stained glass.

In the Part 2 of this series, I mentioned how the use of stained glass in the Salt Lake Temple--particularly the window of the First Vision in the Holy of Holies--helped contribute to the use of stained glass in chapels, as large, magnificent copies of the windows were placed in chapels in Salt Lake that eventually extended to other chapels along the Mormon Corridor. Prior to that time, most stained glass depictions had been fairly simple in design, due to financial constraints; the copies of the window in the temple marked the start of a new era in stained glass, when larger, more expensive, and more ornate windows graced LDS chapels.

|

| Brigham City 3rd Ward |

However, during the peak era of stained glass in chapels (1900-1940), stained glass was not used in temples. Temples in St. George and Manti did not have stained glass; the Logan Temple had some stained glass, but this was likely not original to the building (I believe it was added sometime in the early 20th century. The Manti Temple also has some stained glass in the cafeteria, but this is not original to the building).

|

| Stained Glass in Logan Temple Sealing Room |

Similarly, the temples in Cardston, Laie, Mesa, Idaho Falls, Switzerland, Los Angeles, New Zealand, London, Oakland, Ogden, and Provo--temples built between 1919 and 1972--had no stained glass. (Again, the Laie Hawaii and Idaho Falls Temple now have stained glass, but I don't believe this was original; if it was, these temples were the exceptions.) While stained glass was flourishing in LDS chapels (at least, comparative to other eras), it wasn't present in temples. I believe this was due to the way that the Church viewed its architecture at the time. Chapels, when possible, mimicked the traditional great cathedrals--gothic arches, corner towers, delicate stained glass. Temples were an architecture all of their own; more attention was paid to room arrangement and symbolism than the need for stained glass. Additionally, temples were much larger than chapels; they would require much more stained glass to replace all of their windows. Finally, general architectural trends were going away from the use of stained glass after 1950. The Church is often criticized for phasing out the use of stained glass, but it was happening in multiple denominations. Whatever the reason, no stained glass was used in those temples.

|

| Mesa Arizona Temple (Image Source: LDS Church Temples) |

The temple in Washington D.C. (dedicated in 1974) was among the first to introduce the use of stained glass again, having tall, narrow windows of stained glass along the end. Unsurprisingly, this came at a time when the Church had centralized its meetinghouse architecture, which all but eliminated the use of stained glass in chapels. Modern stained glass was added to the Tokyo Japan and Jordan River Temples (dedicatd in 1980 and 1981, respectively), as well.

|

| Washington D.C. Temple Window (Image Source: LDS Church Temples) |

|

| Tokyo Japan Temple Window (Image Source: LDS Church Temples) |

These steps to re-introduce the use of stained glass were threatened in April 1980, when the Church announced the use of a new standard plan for its temples. This was the beginning of the Church's emphasis on bringing the temples to the people; when the temples were announced, the Temple Department's directors said that “We’ve entered a new era of temples...The emphasis now is on the locality. A different type of sacrifice will be required of people.” Instead of large, cathedral-like temples--which were much more likely to have stained glass put into them--smaller, more economical ones were built. After the announcement, one writer worried: "[The temple standard plan] could eventually establish a new relationship between temple and meetinghouse architecture. Whereas previous architectural style, size and materials had distinguished the temple from the ward meetinghouse, the new temples narrow the gap between these two main forms. The exterior of the temples in no way reveals the unique ceremonies within, and they have no visual articulation, towers, stained glass art windows or other features to distinguish their sacred functions..." Fortunately, a later revision to the plan added towers to the buildings, and some of them even got some form of stained glass windows.

|

| Atlanta Georgia Temple (Image Source: LDS Church Temples) |

Still, the majority of temples built in the 1980s did not have stained glass. The "six-spire" standard plan, which can be seen in temples from South Africa to Guatemala, did not have stained glass windows. The plan for local temples might have wiped out stained glass from future temples if it weren't for a shift around 1990. Temples in Denver, Toronto, Las Vegas, and San Diego all had stained glass installed. In fact, virtually every temple after the Las Vegas Temple (dedicated in late 1989) has had stained glass in some form. This was right around the era that Gordon B. Hinckley was taking charge in temple policy for the Church--either as president himself, or acting in behalf of Ezra Taft Benson, who was ill in his old age. Whether the change came from Hinckley, from new plans in the Temple Department, or from other sources, stained glass suddenly became a necessity in the Church. It could be that the finances of the Church had improved enough to allow stained glass in nearly all temples.

|

| Las Vegas Nevada Temple Window (Image Source: LDS Church Temples) |

This was fortunate, because it meant that most of the very small temples--dedicated around 2000, when the Church initiated a push to have 100 temples--had some form of stained glass. Of course, these windows were fairly simple, and nearly identical between temples.

|

| Columbus Ohio Temple (Image Source: LDS Church Temples) |

|

| Medford Oregon Temple Windows (Image Source: LDS Church Temples) |

However, it should be noted that most of the stained glass now placed in temples is patterned glass--it is much rarer to have stained glass depicting scenes, as was common at the beginning of the twentieth century. There are some exceptions; however. The Palmyra Temple has a window depicting the First Vision.

|

| Palmyra New York Temple Window |

The Winter Quarters Temple has icons and scenes that add to the temple's symbolism.

|

| Winter Quarters Celestial Room Window (Image Source: LDS Church Temples) |

The Nauvoo Temple has a stained glass window in its baptistry showing Christ's baptism.

|

| Nauvoo Illinois Temple Window |

The Manhattan Temple has a window showing Christ and two disciples on the road to Emmaus.

|

| Manhattan New York Temple Window |

The temple in San Antonio Texas has huge, colorful windows in many places that show scenes symbolic of different aspects of the Gospel of Jesus Christ.

|

| San Antonio Texas Temple Window (Image Source: LDS Church Temples) |

And the temple in Sao Paulo Brazil had a stained glass scene installed during its 2004 renovation, depicting Christ appearing in the Americas.

Other temples had stained glass installed from different churches--temples in Vernal, Snowflake, Star Valley, and other locations have stained glass that came from different denominations. The Church has since acquired these windows and used them.

|

| Star Valley Wyoming Temple Lobby (Image Source: Mormon Newsroom) |

I am glad that the use of stained glass has returned to temples, with only two concerns: one is that the use of stained glass to depict scenes has declined drastically in recent history. If you exempt the windows that the Church acquired and used from other churches, then the last temple to use stained glass in this way was the temple in San Antonio, Texas--built in 2005. Even those scenes do not have people in them. The Church uses stained glass, but only patterned glass. Why have we shifted away from the stained glass depicting Christ, the First Vision, and other scriptural stories?

|

| Payson Utah Temple Celestial Room (Image Source: Mormon Newsroom) |

Of course, this week's release of images of the temple in Paris, France revealed a stained glass window of Christ, so unless this was also purchased from another denomination (which I doubt--it looks too modern), this bucks the trend. This is encouraging.

|

| Paris France Temple Window Detail (source: Mormon Newsroom) |

The other concern is that almost all of the Church's stained glass in recent history--especially the windows depicting events--comes from Tom Holdman studios. Holdman does good work, and its Mormon background probably makes it a safe option for the Church, but I worry that we are taking away from the diversity of art in the Church by only using one place for most of our stained glass.

***

The typical Latter-day Saint, when asked about the use of stained glass in the Church, says that its use is reserved for temples, to indicate the hierarchy of architecture in the Church: temples, chapels, other buildings. Some even say that stained glass is not appropriate for ward meetinghouses--it is distracting, or it is uncomfortably close to the architecture of other religions; some even say that any image in the chapel is inappropriate, as it is similar to worshipping idols. In one interview, the late Apostle L. Tom Perry said that "Now, the reason we don’t have pictures or murals in our chapels any longer is that the chapels were made to be places of worship. When we have an art exhibit in front, then everyone is becoming an expert on art and has their own opinions. But the main reason is that we wanted them to be houses of worship and not have the decorative pictures in front. That has been a standing policy of the Church for a number of years now."

|

| Salt Lake Twenty-first Ward Classroom |

It is unfortunate that the Church felt like stained glass and paintings had to be taken away to create a more reverent and sacred experience. Ward members attending chapels where historic stained glass can be found certainly disagree; in my visits to these chapels to document the windows, local members always expressed pride in the stained glass and mentioned their beauty and how it contributed to their spiritual experience.

|

| Salt Lake Twenty-Seventh Ward Windows |

The Church may never again enter a period where stained glass is used in ward chapels. Even if that is the case, it would be worse if we as a Church forget our heritage and identity in the stained glass realm. My greatest hope is that this story helps us remember the fact that we used stained glass, that it was perfectly appropriate (desirable, even), that it contributed to our cultural identity as a Church, and that we could create beauty--Mormon beauty--out of panes of colored glass.

|

| Salt Lake Second Ward Chapel |

Monday, April 3, 2017

Latter-day Stained Glass: Part 9 – Modern Uses of Historic Stained Glass

Note: This is a part of a series on the history of the use of stained glass in LDS meetinghouses. To see a full list of the posts in this series, click here.

In many cases, historic buildings that contain stained glass have been carefully preserved, allowing members to enjoy the windows in the setting for which they were designed. The Church keeps track of its historic properties that are considered protected; many of its most significant stained glass windows are therefore safe from demolition or renovation.

This is not the case for all stained glass, however. As we have noted, many wonderful buildings with stained glass were demolished or sold. Sometimes the stained glass was destroyed or sold along with the building; sometimes, as with the Cedar City Second Ward, it was put into storage. The future use of such glass is unknown.

In other examples, the Church has taken the stained glass and displayed it in various exhibits, either in the Church History Museum or other locations. This is the case for stained glass that stood in the Adams (California), Salt Lake 12th, and Salt Lake 14th Wards.

The confusing lack of a clear policy on what to do with stained glass becomes clear when we look at how the Church treated the windows it decided (for one reason or another) to keep. The windows are treated in a confusing manner, and many examples are still evident.

An early example can be found in the Salt Lake 17th Ward. When it came time to destroy the original Gothic building that housed a First Vision window, the Church built a custom designed chapel with Gothic influences to house the ward and its window.

Even though it was designed specially for the window, the building falls far short of its predecessor. It's style is too modern to properly complement the arched window; furthermore, the window, while placed against an exterior wall, was backed with a black shade to prevent sunlight from filtering through. Electricity is instead used to light the glass from behind, but these lights do not fully illuminate the window.

Interestingly enough, this is a recurring issue for stained glass that was moved into new buildings. The Coalville Stake Center was also specially designed with the three large stained glass panels from the original tabernacle in mind. Two of the windows were placed on either side of the chapel, and the third was placed behind the pulpit--as a picture, not as a window. No light passes through; the panes are not illuminated, either naturally or electronically. This is disappointing and perplexing.

The pattern is repeated in many other places. Windows from the Lehi Fourth and LeGrande Wards were placed in otherwise modern chapels; they are lit electronically. To be fair, these buildings were not exactly designed for the windows. The Lehi Fourth Ward window could have been made into an actual window (with sunlight used to light it), but the LeGrande Ward is against an interior wall (as is the case with many modern chapels) and this wasn't possible.

It appears that the Church is wary about allowing windows in the chapel to be lit naturally, at least when they are behind the pulpit. Perhaps there is a fear that the incoming light will be distracting from the speaker, or make it difficult to view them.

This may be a legitimate fear, but the light from stained glass shouldn't be overwhelming if the building matches the architecture. For example, windows from the Salt Lake Twenty-first Ward were moved into their modern chapel. The original building was smaller and had thick, red brick walls that absorbed much of the light; now, the chapel is much larger with the standard white brick, which produced what Joyce Janetski called "a harsh glare."

All of this points to a recurring problem--the stained glass windows often beautifully fit their original buildings; when they are shoehorned into modern buildings, they can still be appreciated, but not nearly as much as they originally were. The Provo Third Ward's windows were moved into a modern chapel, but the building simply cannot do these windows justice; it is too modern.

The Provo Third and Salt Lake Twenty-first Wards also highlight another problem--confusion about where to put the stained glass in the new building. The Provo Third Ward, for example, put some of the stained glass in the chapel, and put the remainder in classrooms on the west and north sides of the building. The rest of the building was given standard frosted glass. This reduces the effect of the stained glass; it looks like it was just placed wherever it would fit.

Similarly, the Salt Lake Twenty-first Ward had its clear glass panels placed in the chapel, but there were three colored glass panels that also needed to be moved. One was placed in the primary room; the other two were placed in two of the classrooms on the building's south side. The other rooms have plain glass. By separating the stained glass into almost random areas of the building, viewers cannot appreciate the effect of the stained glass together, as it was originally intended, either from the exterior or the interior.

This problem is highlighted even more with other cases. The tabernacle in La Grande, Oregon had some beautiful stained glass. The windows were saved when the tabernacle was demolished; they were then placed in new and exiting chapels in La Grande, Pilot Rock, Elgin, Pendleton, Enterprise, Halfway, and Baker (all nearby towns). This can be seen as a chance to allow more members to enjoy the windows, but by splitting up the windows, nobody can enjoy the full effect that was intended by having all of the windows together. It doesn't fit any architectural style to put two stained glass windows in an otherwise modern building. Before, a stake could savor the complete architectural effect; now, many wards get a small glimpse of what was to be enjoyed.

Other examples show similarly confusing results. The Stratford Ward was given stained glass from the old Cottonwood Ward building; it was installed over the west entrance and in the baptistry. The windows are beautiful, but they were simply placed wherever it was most convenient for them to fit.

The windows in the Millcreek Ward originally consisted of some beautiful old glass on the sides of the chapel, along with two windows of Christ as the Good Shepherd--both at the front of the chapel; one faced outward, and one inward. Now, the original glass on the sides of the chapel are gone, and both panes were moved into the lobbies of a modern building (a rather confusing place to have stained glass). The original, exterior window lost some of its side panels that extended the pastoral scene.

The Murray First Ward is a particularly confusing case. Much of the glass was used as door panels in the building.

The main window, depicting Christ above the words "Come Unto Me," was placed at the front of the chapel. However, it cannot be enjoyed by ward members, because a large organ is also at the front, completely covering the front wall. The organ also prevents light from the chapel to pass through the window, so it is electronically lit. Of course, this is only appreciated at night, so the window is only fully viewed when members happen to have activities after the sun has gone down--not during the regular meetings on the Sabbath.

Joyce Janetski summed up the disappointing effects of moving stained glass as follows:

"In this circumstance architecture has failed to promote its heritage of stained glass by either ignoring or perverting qualities once honored by its creators. Where arhitecture has failed altogether, requiring storage of the glass for an indefinite period period of time, panels of art glass await a resurrection to a life, not possibily butter, but at least as good as the one they had enjoyed. Perhaps better off in a state of limbo, the 'outdated' stained glass pieces may at last come to be realized as Architecture and as Art..." (Joyce Janetski, "A History, Analysis, and Registry of Mormon Architectural Art Glass in Utah," Masters Thesis, June 1981).

Next Week: The Future of Stained Glass

In many cases, historic buildings that contain stained glass have been carefully preserved, allowing members to enjoy the windows in the setting for which they were designed. The Church keeps track of its historic properties that are considered protected; many of its most significant stained glass windows are therefore safe from demolition or renovation.

This is not the case for all stained glass, however. As we have noted, many wonderful buildings with stained glass were demolished or sold. Sometimes the stained glass was destroyed or sold along with the building; sometimes, as with the Cedar City Second Ward, it was put into storage. The future use of such glass is unknown.

|

| Cedar City Second Ward Window |

In other examples, the Church has taken the stained glass and displayed it in various exhibits, either in the Church History Museum or other locations. This is the case for stained glass that stood in the Adams (California), Salt Lake 12th, and Salt Lake 14th Wards.

|

| Adams Ward Window, now in Church History Museum |

The confusing lack of a clear policy on what to do with stained glass becomes clear when we look at how the Church treated the windows it decided (for one reason or another) to keep. The windows are treated in a confusing manner, and many examples are still evident.

An early example can be found in the Salt Lake 17th Ward. When it came time to destroy the original Gothic building that housed a First Vision window, the Church built a custom designed chapel with Gothic influences to house the ward and its window.

|

| Original Salt Lake Seventeenth Ward Building (Image Source: Church History Library) |

|

| Current Salt Lake Seventeenth Ward Building |

Even though it was designed specially for the window, the building falls far short of its predecessor. It's style is too modern to properly complement the arched window; furthermore, the window, while placed against an exterior wall, was backed with a black shade to prevent sunlight from filtering through. Electricity is instead used to light the glass from behind, but these lights do not fully illuminate the window.

|

| Salt Lake Seventeenth Ward Window |

Interestingly enough, this is a recurring issue for stained glass that was moved into new buildings. The Coalville Stake Center was also specially designed with the three large stained glass panels from the original tabernacle in mind. Two of the windows were placed on either side of the chapel, and the third was placed behind the pulpit--as a picture, not as a window. No light passes through; the panes are not illuminated, either naturally or electronically. This is disappointing and perplexing.

|

| Coalville Stake Center Chapel |

|

| Coalville Stake Center Window |

The pattern is repeated in many other places. Windows from the Lehi Fourth and LeGrande Wards were placed in otherwise modern chapels; they are lit electronically. To be fair, these buildings were not exactly designed for the windows. The Lehi Fourth Ward window could have been made into an actual window (with sunlight used to light it), but the LeGrande Ward is against an interior wall (as is the case with many modern chapels) and this wasn't possible.

|

| Lehi Fourth Ward Window |

|

| LeGrande Ward Window |

It appears that the Church is wary about allowing windows in the chapel to be lit naturally, at least when they are behind the pulpit. Perhaps there is a fear that the incoming light will be distracting from the speaker, or make it difficult to view them.

This may be a legitimate fear, but the light from stained glass shouldn't be overwhelming if the building matches the architecture. For example, windows from the Salt Lake Twenty-first Ward were moved into their modern chapel. The original building was smaller and had thick, red brick walls that absorbed much of the light; now, the chapel is much larger with the standard white brick, which produced what Joyce Janetski called "a harsh glare."

|

| Salt Lake Twenty-first Ward Building |

|

| Salt Lake Twenty-first Ward Chapel |

All of this points to a recurring problem--the stained glass windows often beautifully fit their original buildings; when they are shoehorned into modern buildings, they can still be appreciated, but not nearly as much as they originally were. The Provo Third Ward's windows were moved into a modern chapel, but the building simply cannot do these windows justice; it is too modern.

|

| Original Provo Third Ward Building (Image Source: Church History Library) |

|

| Current Provo Third Ward Building |

|

| Provo Third Ward Building |

The Provo Third and Salt Lake Twenty-first Wards also highlight another problem--confusion about where to put the stained glass in the new building. The Provo Third Ward, for example, put some of the stained glass in the chapel, and put the remainder in classrooms on the west and north sides of the building. The rest of the building was given standard frosted glass. This reduces the effect of the stained glass; it looks like it was just placed wherever it would fit.

|

| Provo Third Ward Windows |

Similarly, the Salt Lake Twenty-first Ward had its clear glass panels placed in the chapel, but there were three colored glass panels that also needed to be moved. One was placed in the primary room; the other two were placed in two of the classrooms on the building's south side. The other rooms have plain glass. By separating the stained glass into almost random areas of the building, viewers cannot appreciate the effect of the stained glass together, as it was originally intended, either from the exterior or the interior.

|

| Salt Lake Twenty-first Ward Window |

|

| Salt Lake Twenty-first Ward Primary Room |

This problem is highlighted even more with other cases. The tabernacle in La Grande, Oregon had some beautiful stained glass. The windows were saved when the tabernacle was demolished; they were then placed in new and exiting chapels in La Grande, Pilot Rock, Elgin, Pendleton, Enterprise, Halfway, and Baker (all nearby towns). This can be seen as a chance to allow more members to enjoy the windows, but by splitting up the windows, nobody can enjoy the full effect that was intended by having all of the windows together. It doesn't fit any architectural style to put two stained glass windows in an otherwise modern building. Before, a stake could savor the complete architectural effect; now, many wards get a small glimpse of what was to be enjoyed.

|

| La Grande Oregon Tabernacle (Image Source: Church History Library) |

|

| Elgin Oregon Ward with window from La Grande Tabernacle (Image Source: Church History Library) |

Other examples show similarly confusing results. The Stratford Ward was given stained glass from the old Cottonwood Ward building; it was installed over the west entrance and in the baptistry. The windows are beautiful, but they were simply placed wherever it was most convenient for them to fit.

|

| Stratford Ward |

The windows in the Millcreek Ward originally consisted of some beautiful old glass on the sides of the chapel, along with two windows of Christ as the Good Shepherd--both at the front of the chapel; one faced outward, and one inward. Now, the original glass on the sides of the chapel are gone, and both panes were moved into the lobbies of a modern building (a rather confusing place to have stained glass). The original, exterior window lost some of its side panels that extended the pastoral scene.

|

| Millcreek Ward Exterior Window (Image Source: Church History Library) |

|

| Millcreek Ward Window |

The Murray First Ward is a particularly confusing case. Much of the glass was used as door panels in the building.

|

| Murray First Ward Chapel Doors |

The main window, depicting Christ above the words "Come Unto Me," was placed at the front of the chapel. However, it cannot be enjoyed by ward members, because a large organ is also at the front, completely covering the front wall. The organ also prevents light from the chapel to pass through the window, so it is electronically lit. Of course, this is only appreciated at night, so the window is only fully viewed when members happen to have activities after the sun has gone down--not during the regular meetings on the Sabbath.

|

| Murray First Ward Chapel |

|

| Murray First Ward Window |

Joyce Janetski summed up the disappointing effects of moving stained glass as follows:

"In this circumstance architecture has failed to promote its heritage of stained glass by either ignoring or perverting qualities once honored by its creators. Where arhitecture has failed altogether, requiring storage of the glass for an indefinite period period of time, panels of art glass await a resurrection to a life, not possibily butter, but at least as good as the one they had enjoyed. Perhaps better off in a state of limbo, the 'outdated' stained glass pieces may at last come to be realized as Architecture and as Art..." (Joyce Janetski, "A History, Analysis, and Registry of Mormon Architectural Art Glass in Utah," Masters Thesis, June 1981).

|

| Murray First Ward Window |

Next Week: The Future of Stained Glass

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)